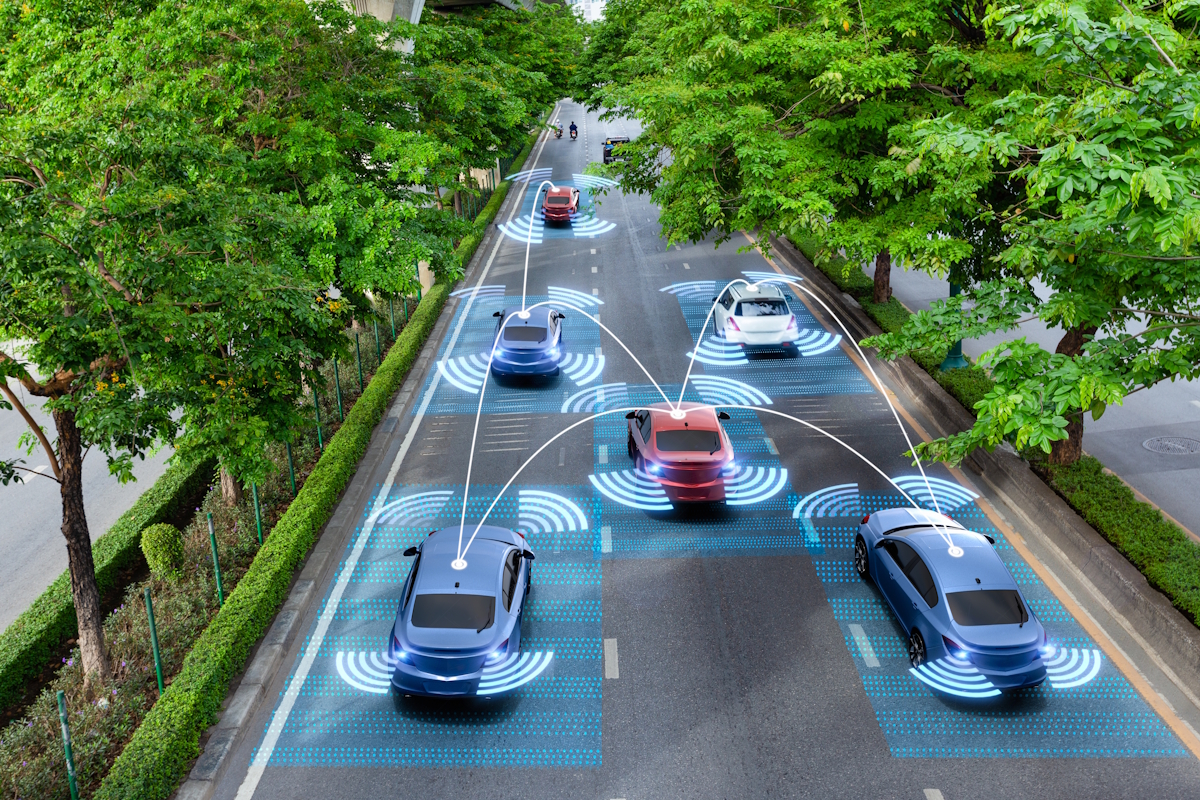

Urban mobility is becoming a programmable urban function, shaped in real time by data, connectivity, and automated control. As vehicles, intersections, and traffic management systems begin to communicate continuously, cities are moving beyond isolated upgrades toward integrated mobility platforms that can anticipate demand, prevent incidents, and allocate street capacity with precision. Cooperative mobility networks, enabled by V2X communications, edge computing, and AI-driven orchestration, are emerging as a defining layer of smart city infrastructure, linking transport performance directly to safety, emissions, resilience, and the everyday experience of moving through the city

The next phase of urban mobility is defined less by the performance of individual vehicles and more by the computational integration of vehicles, infrastructure, and public systems into a coordinated urban platform. In this model, mobility becomes a cyber-physical service continuously shaped by real-time data, distributed intelligence, and automated control loops that span roads, intersections, public transport corridors, logistics routes, and pedestrian environments. The strategic objective is not merely to reduce travel time, but to transform the city into an adaptive system capable of sensing conditions, interpreting intent, forecasting demand, and optimizing movement as a shared resource. As cities pursue smart city agendas, cooperative mobility networks increasingly serve as a core layer of urban digital infrastructure, comparable in importance to energy distribution, water management, and telecommunications. Mobility, once managed through static rules and periodic planning cycles, is being re-engineered as a responsive, software-defined domain in which operational decisions are computed continuously and enacted through connected assets.

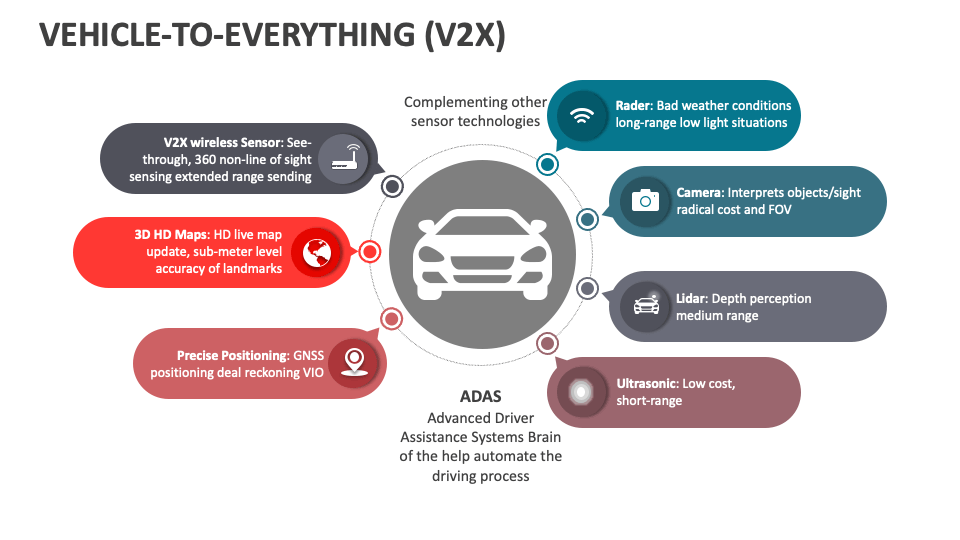

At the technical center of this transformation is Vehicle-to-Everything communication, a framework that enables vehicles to exchange structured messages with other vehicles, roadside units, traffic control systems, network services, and vulnerable road users. Vehicle-to-Vehicle communication supports cooperative awareness by sharing speed, heading, braking events, and trajectory predictions. Vehicle-to-Infrastructure communication links vehicles to signal phase and timing, variable speed limits, lane control systems, work zone advisories, and digital signage. Vehicle-to-Network services extend this interaction into cloud and edge platforms where broader situational context can be computed, including corridor-level congestion forecasts, incident detection, and multimodal routing. In practice, V2X becomes the communications substrate for intelligent transportation systems, enabling data to move between distributed endpoints with latency and reliability characteristics suited to safety-critical use cases. Depending on regional deployments and regulatory choices, V2X may be implemented through cellular-based approaches such as C-V2X over 4G and 5G, legacy dedicated short-range communications, and hybrid architectures that integrate both. Regardless of the radio technology, the smart city value emerges from the operational layer built above connectivity, where sensor inputs are normalized, trust and identity are established, and decision logic is executed consistently across public and private fleets.

Smart infrastructure provides the fixed, city-managed counterpart to connected vehicles by embedding sensing, computation, and communication into the built environment. Intersections can be equipped with radar, LiDAR, cameras, inductive loops, and environmental sensors to observe traffic states, detect near misses, and recognize priority vehicles or pedestrians. Roadside compute nodes can perform local inference to reduce latency and bandwidth consumption, enabling rapid actions such as extending a green phase for a bus running late or issuing a hazard warning when a vehicle is detected traveling the wrong way. When integrated with adaptive signal control systems, these capabilities allow signal timing plans to evolve dynamically based on measured demand, downstream occupancy, and corridor coordination targets. This is a decisive shift from the traditional approach of optimizing isolated intersections toward the orchestration of network performance under changing conditions, including weather events, stadium traffic, construction impacts, and emergency response. The infrastructure becomes an active participant in mobility, not a passive surface, and its modernization becomes a foundational component of smart city development, requiring civil engineering, power supply upgrades, telecommunications backhaul, and lifecycle maintenance strategies that treat digital components as critical assets.

Artificial intelligence and advanced analytics make cooperative mobility networks operationally meaningful by converting raw data into predictions, priorities, and control actions. Modern cities generate high-volume mobility telemetry from vehicles, smartphones, transit systems, parking facilities, curbside sensors, cameras, and connected signals, yet the strategic advantage lies in fusing these heterogeneous streams into a consistent representation of the urban state. Machine learning models can forecast congestion formation, estimate queue lengths, identify abnormal patterns indicative of incidents, and infer travel demand shifts in near real time. Predictive control approaches can then adjust signal offsets, meter ramp flows, recommend reroutes, and coordinate multimodal transfers, with objectives that combine efficiency, safety, emissions reduction, and equity of access. AI also enables anomaly detection and predictive maintenance for infrastructure, such as identifying failing signal controllers, degraded pavement conditions, or sensor drift before outages occur. In smart city terms, cooperative mobility becomes an example of closed-loop urban management, in which sensing, reasoning, and actuation are tightly coupled and continuously refined as new data arrives.

Connected and increasingly automated vehicles amplify these gains when they operate as cooperative agents within the broader system rather than as independent automated units. Autonomy depends on onboard perception and planning, but its performance improves substantially when vehicles receive infrastructure-provided context such as upcoming signal states, recommended speeds for green-wave progression, work zone geometry, temporary lane shifts, and verified hazard alerts. Conversely, vehicles can contribute high-fidelity observations back to the city, including friction estimates during rain, sudden braking clusters indicating near-collision zones, and lane-level travel time measurements that exceed the resolution of conventional detectors. This reciprocal exchange enables collective perception and cooperative maneuvering, where the environment is understood not only through each vehicle’s sensors but through a shared situational model supported by infrastructure sensing and network analytics. As a result, safety is addressed not solely through driver assistance or automation features, but through systemic risk reduction achieved by coordinated information flows and harmonized responses across the traffic network.

The smart city impact extends beyond private vehicles to public transport, micromobility, and freight, which are increasingly coordinated through integrated mobility platforms. Buses and trams can be granted conditional priority at signals based on schedule adherence, passenger loads, and corridor capacity, allowing cities to improve reliability without indiscriminately delaying cross traffic. Demand-responsive transit and shared mobility services can be guided through dynamic routing and curb allocation policies that reduce conflicts and illegal stopping. Freight operators can participate in time-windowed access and geofenced delivery zones, with routing optimization that accounts for curb availability, low-emission districts, and real-time restrictions. When these elements are combined under a multimodal management framework, the city can shift from managing vehicles to managing flows, allocating right-of-way and curb space in response to measured demand and policy objectives. In this context, cooperative mobility networks become instruments of urban transformation, enabling land-use goals such as reduced parking dependence, improved walkability, and lower emissions by making alternative modes more reliable and by reducing the systemic inefficiencies that discourage mode shift.

Achieving this level of coordination requires robust digital architecture, typically combining edge computing, cloud services, and standardized data models that support interoperability across vendors and jurisdictions. Edge nodes located near intersections and corridors can execute latency-sensitive functions such as collision warnings, signal control, and local sensor fusion, while cloud platforms handle citywide optimization, historical analysis, and long-horizon forecasting. Digital twin technologies increasingly complement these operational systems by providing simulation environments calibrated with live data, allowing agencies to test signal strategies, construction phasing, and policy scenarios before deployment. Standardized interfaces for traffic signal controllers, roadside units, mapping layers, and mobility service providers are essential to avoid fragmented ecosystems in which each corridor or fleet becomes a silo. The long-term smart city objective is a modular, vendor-agnostic stack in which core functions can evolve over time without forcing wholesale replacement of infrastructure. This is both a technical and governance requirement, since procurement strategies, data-sharing agreements, and operational responsibilities must be aligned with architectural choices to ensure continuity and scalability.

The same connectivity that enables cooperative mobility also expands the attack surface and heightens the importance of cybersecurity, privacy engineering, and trustworthy governance. Safety-critical messages must be authenticated, integrity-protected, and resilient to spoofing, jamming, replay, and malicious injection. Identity and credential management frameworks are required to ensure that vehicles, roadside units, and back-end services can participate securely while limiting unnecessary disclosure of personal information. Privacy risks arise when location traces, vehicle identifiers, and behavioral signals can be linked to individuals, especially when mobility data is combined with other urban datasets. Smart city deployments therefore demand clear rules on data minimization, retention, access control, and purpose limitation, as well as transparency mechanisms that allow public oversight. Governance is equally critical in determining how public agencies and private operators share responsibilities, how service-level targets are enforced, and how algorithmic decisions are audited for bias and unintended impacts. Without these safeguards, the same systems designed to optimize traffic and improve safety can erode public trust and create unacceptable societal risks.

Interoperability and standardization remain decisive factors because cooperative mobility is inherently cross-boundary. Vehicles travel between municipalities, regions, and countries, and fleets are produced by diverse manufacturers using different software stacks. For cooperative mobility to function at scale, participants must exchange messages using common semantics and compatible security frameworks, and infrastructure deployments must be maintained consistently over time. This necessitates alignment on communication profiles, message sets, performance requirements, and conformance testing, along with operational standards for how cities publish signal timing information, work zone data, and restrictions. Just as the internet depends on shared protocols to ensure universal reachability, smart mobility depends on shared technical and governance protocols to ensure that connected vehicles can interact safely and predictably across heterogeneous environments. The transition is not solely a matter of adopting new devices; it is the implementation of a reliable, standardized, and evolvable urban communications and control layer.

Ultimately, connected vehicles and smart infrastructure represent a practical pathway for cities to convert mobility from a reactive service into a programmable urban function, tightly integrated with broader smart city systems such as energy management, environmental monitoring, public safety, and emergency response. Cooperative mobility networks turn streets into data-producing assets, intersections into decision points, and traffic management centers into orchestration hubs that balance competing objectives in real time. When deployed with mature digital architecture, secure governance, and interoperable standards, these networks enable cities to operate as adaptive systems that learn from their own behavior, anticipate disruptions, and allocate capacity with greater precision. In that sense, cooperative mobility is not only an innovation in transportation technology, but a core mechanism through which cities modernize their infrastructure, institutional capabilities, and operational intelligence, accelerating the broader transformation toward smart cities defined by measurable performance, resilience, and continuous optimization.